In the grand tapestry of history, the Gilded Age unfurls as a captivating backdrop, casting a shadow of stark contrasts upon the canvas. Here, prosperity dances with danger, ambition grapples with criminality, and progress strides hand in hand with duplicity.

Against this evocative historical stage, Erik Larson’s “The Devil in the White City” invites us to a narrative where the Gilded Age provides the hauntingly enchanting setting, and at its forefront, stand two central figures: Daniel Burnham and H.H. Holmes. As we embark on this journey, we’ll traverse the delicate tightrope of ambition and peril, and witness the interplay of light and darkness that defined this era.

As Larson guides us through this enthralling narrative, he prefaces our journey with a chilling disclaimer that ends with the following paragraph:

“Beneath the gore and smoke and loam, this book is about the evanescence of life and why some men choose to fill their brief allotment of time engaging the impossible, others in the manufacture of sorrow. In the end it is a story of the ineluctable conflict between good and evil, daylight and darkness, the White City and the Black.”

Devil in the White City, xi.

At the heart of this narrative, we encounter three central groups of characters. First, there is Daniel Burnham and his cadre of visionary architects, individuals driven by ambition, fame, and the pursuit of success. Second, the enigmatic H.H. Holmes emerges, a master of charm and manipulation, whose tale is closely entwined with that of his unsuspecting victims. And finally, the backdrop of society at large, where progress stands hand in hand with a gaping wealth gap, unfolds as a powerful character in its own right.

In this analysis, we journey through the parallel narratives of Daniel Burnham’s pursuit of progress and H.H. Holmes’s descent into criminality. “The Devil in the White City” vividly portrays the Gilded Age, marked by ambitious progress and lurking danger. It’s an era where society’s stark duality blends light and darkness, where the pursuit of greatness often shadows malevolence. This exploration unveils the delicate interplay of ambition, progress, and peril during the Gilded Age, reflecting a society navigating its complexities.

Daniel Burnham & The Architects: Pursuit of Ambition & Progress

At the heart of it all stands Daniel Burnham, a central figure who will mastermind the monumental spectacle that would define an era. Alongside him is his partner, John Root, both acclaimed as the architectural virtuosos of Chicago’s heyday. They not only pioneered the field but also engineered the very first skyscraper that left an indelible mark.

Burnham’s role as the chief architect for the World’s Fair encapsulates the grit and hunger of the period—a time when ambition ran high, dreams reached for the stars, and the desire to orchestrate greatness enveloped every endeavor. Burnham’s ambition was palpable, his dedication unwavering as he shouldered the monumental responsibility of bringing the fair to life.

“Failure was unthinkable. If the fair failed, Burnham knew, the nation’s honor would be tarnished, Chicago humiliated, and his own firm dealt a crushing blow”

Devil in the White City, 33.

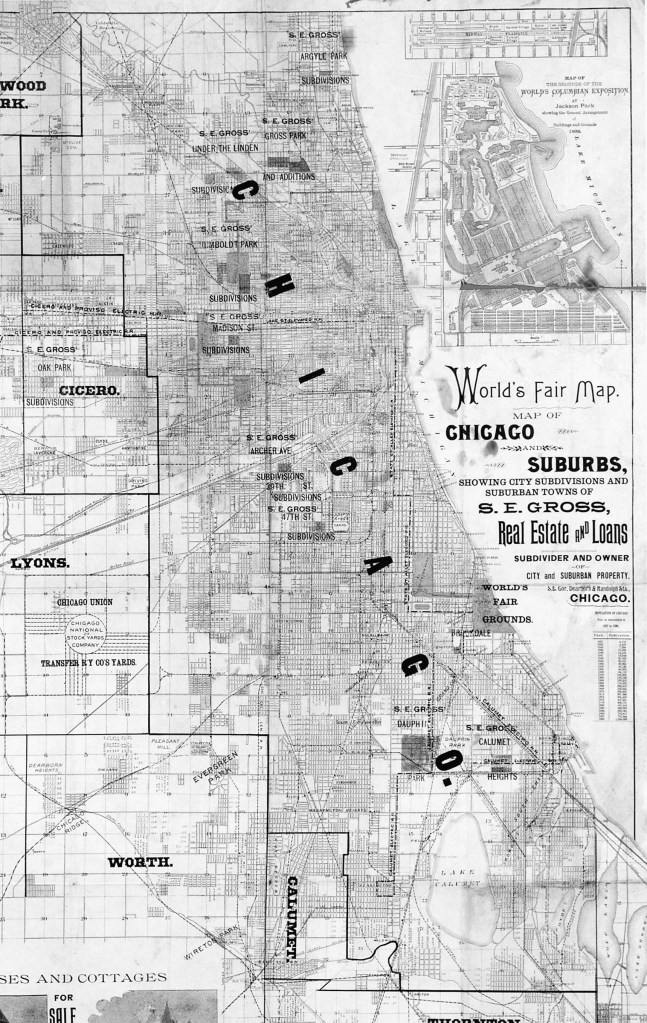

In his pursuit of crafting a grand narrative for the World’s Columbian Exposition, Burnham faced multifaceted challenges. The quest for the perfect location for the exposition consumes about half a year, tightening an already demanding schedule. The dual responsibility of profitability for investors adds an extra layer of complexity. Moreover, Burnham’s uphill battle in enlisting fellow architects in the project initially faces resistance.

Also driven by the need to outshine the Parisian fair that had set the standard, Burnham sought ways to top its extravagance and innovation. Yet, his relentless persistence and unwavering vision pave the path for their eventual involvement, underscoring his remarkable tenacity.

The significance of the World’s Columbian Exposition cannot be overstated. It stood as a symbol of progress and innovation, rising from the ashes of the Great Fire of 1871 that had ravaged Chicago. Burnham held the weight of proving America’s capability to the rest of the world squarely on his shoulders. The Ferris Wheel, a marvel of engineering, highlighted the fair’s extravagance and innovation, while the beauty of the finished product concealed the tragedies and challenges that had built it all.

As we reflect on Burnham’s pursuit of ambition and progress, we must weigh that against the formidable obstacles that stood in his path. The relentless constraints of time and money, the intricate dance of labor management, the ever-present threat of fires in an era without modern safety standards, and the occasional disagreements in vision—all were hurdles that Burnham and his team would need to overcome. In this narrative of ambition and progress, we glimpse the indomitable spirit of an age where dreams soared to unprecedented heights, and where, despite the odds, visionaries like Burnham shaped history.

Holmes’s Dual Nature: Charisma and Dark Deeds

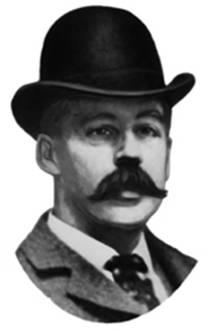

Let’s turn our gaze to Dr. H. H. Holmes—a character of chilling duality who navigated the contrasting realms of charm and ruthlessness with calculated precision. Within the heart of this era, Holmes’s dual identity was a mesmerizing paradox, where his charisma concealed the darkest of intentions.

Born Herman Webster Mudgett, charmed others effortlessly and displayed an uncanny affinity with women. His real name belied the sinister identity he harbored, as he embarked on a twisted journey of criminality while living under the guise of a doctor. This intricate interplay between his professions was a constant in his life.

Holmes’s façade as a charming doctor allowed him to perpetrate his malevolent schemes with disturbing ease. He wielded manipulative tactics like a sinister puppeteer, weaving a web of deceit that ensnared those who crossed his path. His calculated demeanor often crossed the boundaries of societal norms; he would touch too much, too often, leaving his victims unsuspecting of the horrors that lay beneath.

Holmes’s malevolence reached its zenith when he constructed an entire building designed to hide his evil deeds. This macabre structure, known as the “Murder Castle,” was a labyrinth of horrors—a place where the darkest nightmares found form. Holmes’s proficiency in architectural design allowed him to create his own devil’s playground.

Oddly enough, he designed his house of horrors at the same time that Jack the Ripper was going on a murder spree on the other side of an ocean. This eerie coinciding of events paints an ominous picture, hinting at Holmes’s underlying malevolence.

To understand the depths of Holmes’s crimes, we delve into his motivations and the psychological factors that propelled him to commit heinous acts. His insidious cover-ups included financial and insurance schemes that masked his trail of deceit. Holmes even undertook a massive architectural feat, constructing the Murder Castle, to conceal the depths of his devilish deeds.

He preyed upon the vulnerabilities of those who trusted him, targeting unsupervised children and individuals whose disappearances were less likely to raise suspicion—a haunting reflection of a society in transition.

The psychological underpinnings of Holmes’s actions unravel through glimpses of his past. Holmes describes a frightening childhood incident with bullies as the catalyst that drove him toward a career in medicine. However, Larson speculates that it is more likely the bullies ended up terrified of Holmes cold reaction to dead bodies .

As we unravel the harrowing tales of Holmes’s victims, we bear witness to the human tragedies that unfolded during this treacherous period. One such story revolves around a lady whose husband was ailing, and Holmes, initially a savior, ultimately became her demise. We uncover the chilling account of a missing child during Holmes’s tenure as a principal back east—a narrative steeped in darkness.

Even those close to him, including business partners, were not spared, as his treacherous path led to betrayal before the long arm of the law caught up with him. Everyone including Holmes is led to believe that the devil lived within him. Undoubtedly, there was evil. The gas pipes that he installed so he could gas his victims or the massive kiln he had installed. With a creepy story where Holmes investigated to make sure it was sound proof. Disturbing to say the least.

Holmes’s dark actions stand as a reflection of the broader duality that characterized Gilded Age society. Despite his financial means, he brazenly shirked his debts while currying favor with the police. This stark contradiction mirrors the contradictions prevalent in an era of ostentatious prosperity and stark inequality.

Furthermore, his crimes act as a lens through which the vulnerability of individuals in a rapidly changing urban landscape is exposed. Holmes’s financial schemes and intricate manipulations demonstrate how confidence and charisma can render individuals susceptible.

His victims’ willingness to believe in the best of humanity leads them to illogical decisions, driven by the belief that they can gain from the situation or help those they perceive as good-hearted individuals. This resonance between Holmes’s actions and societal vulnerabilities serves as a chilling commentary on the intricacies of the time.

Society at Large: The Gilded Age Duality

The pages of “The Devil in the White City” unveil an era both exhilarating and somber. As we step into the narrative, the vibrant but shadowed backdrop of society during the late 19th century comes to life.

Chicago, a city burgeoning with ambition and promise, serves as the epicenter of the tale, its pulse reverberating through the lives of its inhabitants. It’s a time when changes are sweeping across the nation, notably in the role of women, who are increasingly daring to travel unaccompanied, breaking away from traditional norms.

At its core, the Gilded Age is a complex tapestry woven with threads of rapid industrialization juxtaposed against stark societal disparities. The chasm between the wealthy elite and those struggling to put food on the table is a vivid reminder of the gulf that exists. The era’s grand spectacles—symbolic of its progress—are set against the backdrop of individuals striving to make ends meet. This stark disparity forms the foundation for the contrasting narratives of Daniel Burnham’s ambition and H.H. Holmes’s malevolent crimes.

Architectural innovation stands as a testament to the city’s resilience, particularly evident in Chicago’s prideful recovery following the devastating Great Fire of 1871. The intricate architectural feats showcased in the World’s Columbian Exposition elevate the American identity, exuding an aura of renewal and grandeur. The rapidity with which Chicago was rebuilt fuels the city’s sense of achievement, offering a beacon of hope in the face of adversity.

Unfortunately, the city would have to rebuild portions of the fair and the city multiple times. Take a look at the picture above taken after a storm came through. It is incredibly hard to battle mother nature. The photo below depicts the aftermath of a fire. Theories point to the fire being started by rowdy youngsters.

Prior to any devastation, the allure of the fair captivated the imagination, offering the promise of an economic boost and global recognition. Yet, society grappled with a fear rooted in uncertainty—questions about whether resources might be better invested elsewhere lingered in the minds of many.

The dichotomy of progress versus security reflects the broader tension of the era. The desire to outshine the world is set against the responsibility to ensure stability for Chicagoans amidst the ever-changing landscape.

In the interplay of these contrasts, “The Devil in the White City” illuminates the multifaceted nature of the Gilded Age. This era, characterized by both soaring achievements and daunting challenges, serves as the backdrop against which Burnham’s architectural vision and Holmes’s sinister crimes unfold. The book’s exploration of society at large reveals a tapestry intricately woven with the threads of progress and vulnerability, painting a compelling portrait of a city and its people at the crossroads of history.